Why it's So Challenging to Talk About Difficulty

Why we should talk about the effects of difficulty in games.

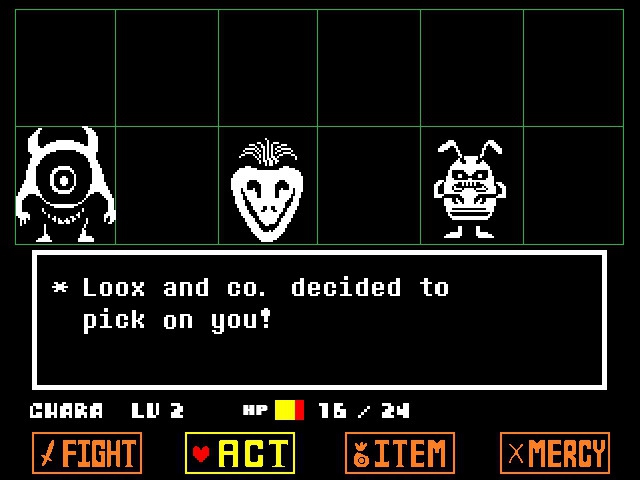

In Undertale, you can choose not to kill any of the game’s strange and endearing monsters. Instead of whacking down their health bars like any other turn-based RPG, you can speak to them or flee. The pacifist route doesn’t come without its own challenges, though. Killing enemies rewards experience and experience levels you up, increasing your total health. Because you can’t avoid the game’s battle mini-game, which is not unlike an arcade bullet-hell shooter, it gets increasingly harder the more you opt out of the violence. Although the game’s marketing description touts the pacifist option as a unique way to play through the game, it doesn’t mention how hard it quickly becomes.

Undertale, through both its narrative and battle system, punishes players who go the non-traditional route. It says that killing is bad and immoral and that the only way to true righteousness is to maintain determination under the extreme disadvantages it gives to you. Only the purest pacifists get the true ending, the ones mentally and physically able to withstand the game’s relentless boss battles. If you want to finish the game as a pacifist and can’t handle it, that’s too bad.

I couldn’t handle it, but my desire to finish the game’s storyline and character arcs was greater than my frustration with insurmountable defeat. So I cheated, artificially raising my health high enough to support my poor ability to dodge projectiles. In the end, I still appreciated where the game went, despite skipping out on its late-game challenges. It gave no reason for me to regret what I’d done, no reason for its difficulty to be so exponentially high for this one path through the game. I’m not alone; Jake Muncy’s review of the game on Killscreen comes to the same conclusion: “Its limited combat options and often obtuse puzzle solving, alongside the sheer endurance required to survive boss fights long enough to end them, add up to a system that doesn't point to any elaborate moral insight.”

Muncy sees the game’s difficulty within the context of the rest of the game. Its hostility toward players who choose the pacifist route, he claims, doesn’t add anything valuable to his experience with it. The stubborn boss battles were simply arbitrary skill requirements, separated from the game’s emotional thrust. It’s a strong criticism of the game, arguing that its central, repeatable action is unnecessary to its ultimate point. It highlights an aspect of games we don’t talk about enough.

Many games demand a certain level of skill from players who want to see everything they have to offer, and sometimes this bars many people from playing them. Dark Souls hides a tragic storyline and stunning imagery behind its stilted user-interface and savage combat. Most people praise the action game for the high of success that naturally follows its grueling battles, but anyone incapable of internalizing the rhythm of its combat and the patience to deduce how its items and stats work, might never know this feeling. League of Legends barricades itself with a different kind of difficulty, one that most of its players admit takes hours to overcome. This massively popular multiplayer game complicates its strategic, player versus player competition with unique characters, abilities, and items. On top of that is a constantly-shifting meta-game that requires a regular presence in the community to stay up-to-date. For someone who lacks the free time or raw skill to tackle these challenges, these games are off-limits.

Games like Dark Souls and League of Legends demonstrate a tricky problem that games as a medium have to wrestle with. How much skill do you expect from your audience? Skill in games is a form of literacy. You must be able to interpret, i.e play a game well enough to engage with it, just as you must be able to read to understand a book. A game’s skill requirement defines who the audience is.

While it would be ridiculous to expect all games to be cakewalks for the purpose of mass-appeal, the pressure to not speak up about the issue on a game-by-game basis seems similarly outlandish. It goes back to the arcades, where skill was measured and boasted by high scores. All that mattered in those games were how good you were at them. That competitive culture still exists today. Say a game is too hard and you’re told that it’s not that hard, that you should just keep trying, or worse, that the game is not meant for you. In most game reviews, you see difficulty mentioned briefly, as a pro or a con, or not mentioned at all. It rarely appears as a criticism connected to the entire experience of the game. Unlike every other aspect of games we regularly discuss, it’s strangely left out, devalued, treated like it doesn’t matter.

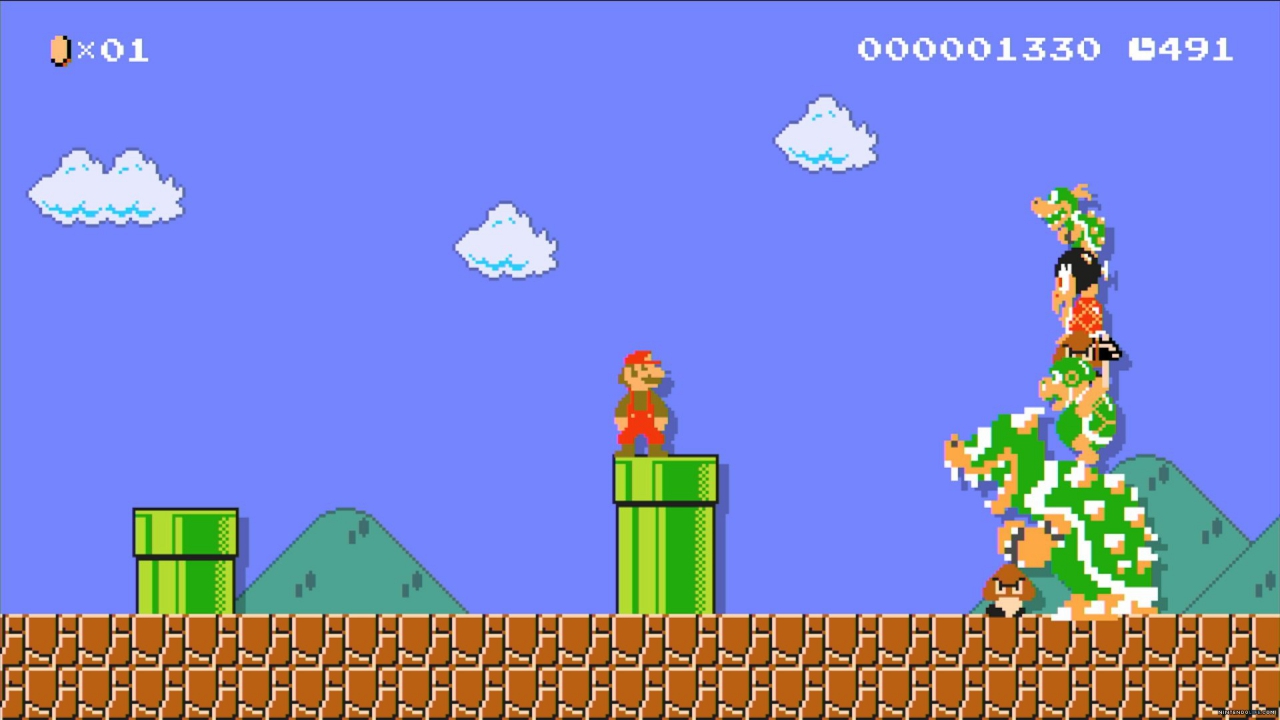

The problem with ignoring difficulty manifests itself in Super Mario Maker, a recently released Wii U game that gives you the tools to build and share your own Mario levels. A significant portion of the top levels in the game’s online list offer almost no challenge at all. Some have deemed these “auto-players,” or levels where you’re carried to the end on a series of conveyor belts and clever drops while admiring their Rube Goldbergian-handiwork. These creations let almost anyone appreciate the beautiful complexity of Nintendo’s long-running series without the threat of dying and having to restart. Of course, intricately hard levels are cropping up too. This last month, thousands of viewers watched the culmination of a rivalry between two game journalists over a series of absurdly tough Super Mario Maker levels. You can see the mix of joy and frustration you get from a devilishly complicated Mario level. The difficulty becomes a puzzle as you test theories and practice sections over and over. Both types of levels, easy and hard, use Super Mario Maker's mechanics in clever ways. They show that there’s a way to appreciate the game, whether you're able to spend hours trying to finish a level or not.

Super Mario Maker is in a unique position to offer both extremes, but it highlights how a player's relationship with difficulty can vary. Just as there are people who thrive off a challenge, there are people who crumble underneath it. It varies from person to person. Games like Undertale can go too far and bar meaningful parts of themselves from players who can't overcome their demands. They can lock away their value behind an arbitrary requirement. That doesn't mean there can't be a valid purpose for a high level of difficulty, but it should come with the understanding that many people play games, and that difficulty isn't universal.

Tyler Colp is a writer who is relentlessly curious about video games, music, cooking, and film.