Birth of the Flight Simulator: Link Goes to War

The world's first flight simulator was standard equipment in WWII -- on all sides.

This column is the second in a two-part series about the Link Trainer, the world’s first flight simulator. You can read part one here.

It took Edwin Link five years to convince the U.S. Army to buy his flight simulator. But in the wake of the Air Mail scandal — with thirteen pilots dead from lack of instrument training — the U.S. Army Air Corps decided the Link Trainer was a good investment. The initial 1934 order of six trainers, at $3,500 a piece, was a coup for Link — but it was only the beginning.

The Army contract catapulted Link Aviation, Inc. onto the defense industry’s radar. The little company, still headquartered out of Binghamton, New York, started receiving orders from the U.S. Navy as well as Tokyo, Moscow, London and Berlin. The Trainer, built in a basement for Link’s amusement, was about to arm the world for the greatest air war in history.

The Link Model C-3: A New Dimension in Simulation

While the initial Link Trainer was revolutionary, Link knew he couldn’t sit on his laurels. By this time, competition from other devices was heating up, and Link needed a machine that could meet the demands of a quickly-modernizing U.S. military.

In 1936 Link introduced the Model C-3, an improvement on the original Link Trainer that turned the simulator from a mere instrumentation tool to what was, essentially, a programmable flight computer.

The C-3 was much like the original Link Trainer — a windowless cockpit mounted on a bellows-operated pivot joint — but instead of the joint being fixed, the whole apparatus sat on a turntable so the model plane could rotate 360 degrees. This enhanced the Trainer’s “feel,” and allowed Link to install a compass for navigation training. The new model also included an altimeter that responded to the stick, meaning the Trainer could simulate ascent and descent without an instructor calling out altitude from outside the cockpit.

But the largest change was the instructor’s station. While the previous Trainer had instructors stand radioing in directions, the Link C-3 had an entire table that let instructors monitor students’ training flights. The table included a radio to communicate with the student, an instrument panel that worked in tandem with the one inside the cockpit, and a large section the instructor could slide maps into, in order to simulate missions. The most novel device was a “crab” — a wheeled triangular mechanism that tracked the student’s flight path on the map, marking his progress in red ink. Not only did this help instructors track if a student was on course, it allowed students to identify their navigation errors after a training session concluded.

But the most amusing improvement — to instructors, at least — were the weather options. The C-3 could simulate rough weather at the push of a button, and if a student pushed the plane outside its flight envelope, the instructor could initiate a stall, making the turntable spin like a carnival ride off its axis. Cadets found these stalls so unpleasant, they were known to bail out rather than try and recover.

Though the stalls were nauseating, crashing in the simulator was infinitely preferable to crashing in the air.

These additions made the Model C-3 a powerful, versatile training tool. Not only could the Link Trainer give students the feel of flying by instruments, it allowed instructors to design pre-set missions that demonstrated specific maneuvers as well as unexpected encounters. Link’s “Pilot Maker” might have simulated peacetime flight, but the C-3 could simulate war.

Arming the World

The U.S. military’s faith in the Link Trainer — and word of the upcoming Model C-3 — boosted Link Aviation’s reputation on the world stage. By 1935, world militaries were re-arming and modernizing, and Link’s address book filled up with foreign officers interested in expanding their country’s air capabilities.

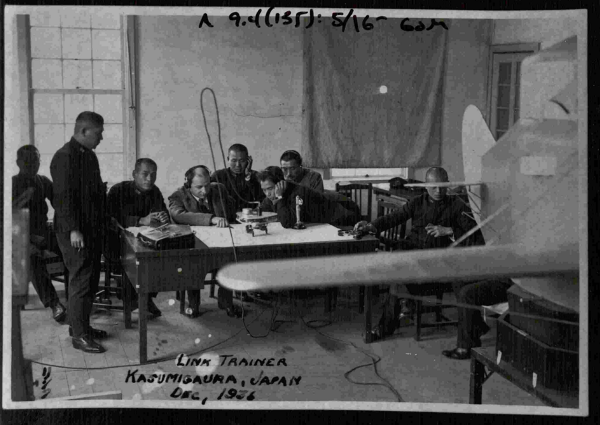

Link’s first international client was the Imperial Japanese Navy, which ordered ten Model C-3’s in 1935. Link and his wife Marion delivered them personally in December 1936, using the business trip as a working vacation. Edwin spent a week introducing Japanese officers to the C-3 before the pair returned on a luxury ocean liner.

Interest heated up in Europe, bringing enough overseas orders that in 1937 Link produced a popular variant trainer with a European instrument layout. By the time the Second World War began, 35 countries — including almost every participating nation — were training their pilots in Link’s machines.

It’s difficult to pin down, except in broad strokes, who was buying Link Trainers during this period. Due to a flood that destroyed the company’s pre-1939 records, family photos are almost the only record of Link Aviation’s pre-war operations. This hole in the data leaves a great deal of questions unanswered — including the extent of Link Aviation’s dealings with Nazi Germany.

It’s a fact that the Luftwaffe purchased, and used, several Model C-3 Trainers. Multiple sources attest that in 1940, German bomber pilots used Link Trainers as part of a “blind flying” certification. But the fact that this training was limited to bomber pilots suggests the Luftwaffe had limited access to the equipment, and probably didn’t have a large compliment of Model C-3s. Indeed, by 1940 the Nazis were training with locally-produced copies instead of genuine C-3s, indicating that Link Aviation, like most (but not all) American companies, cut trade with the Nazis as atrocities mounted in the late 1930s.

There’s little evidence to determine what Edwin Link thought about these overseas sales. Selling training aids to Germany and Japan wasn’t illegal at the time, and given the number of Link Trainers the company sold internationally, it’s hard to interpret small deliveries as a political endorsement. After all, Link sold widely — by 1939, he’d dispatched C-3’s to the USSR, Australia, and even American Airlines, with Britain being his second-largest market. Certainly Allied nations — his largest clients — didn’t see these sales as evidence of disloyalty.

On the other hand, there’s no question blind-flying was a major component of nighttime bombing raids, meaning it’s possible Link Trainers helped target Allied cities like London and Nanjing.

But despite these sales abroad, the U.S. military was always Link’s primary client — and they were about to need him more than ever.

The “Blue Box” Goes to War

Three weeks after the Pearl Harbor attack, Link answered a letter of condolence from a British colleague. “At least one thing the J—s have done, and that is to wake us up in this country,” Link wrote. “Apparently in the Orient they are doing more than waking us up.”

He was right. The Japanese Navy was battering American forces in the Pacific, partially due to their huge advantage in air power. To compete, the United States had to recruit — and train — a massive pilot corps.

And Link had the tool to do it — an improved simulator built specifically for military use. It was called the ANT-18, short for U.S. Army-Navy Trainer. The ANT’s panel specifically mirrored the AT-6 Texan, the U.S. Air Corps’ main training aircraft. A slightly enhanced version of the C-3, the ANT also simulated pre-stall vibrations and over-speed landings. Later models also lacked the Trainer’s yellow wings and tail — casualties of wood rationing — leading pilots to nickname it the “Blue Box.”

The stripped-down fuselage was also easier to produce, and produce, Link did. By the end of the war, Link Aviation Devices pumped out ANT-18’s to fuel the Allied war machine, at one point producing a Trainer every 45 minutes. The British Commonwealth also bought as many as it could, asking Link to open a satellite factory in Canada.

For Link, the war was an intense period. Though American manufacturing benefitted from the government’s large orders, it wasn’t easy to square the patriotic mass-production of total war with the economics of running a business. Constant production also stretched employee morale, with over-stressed workers shaving time off their shifts or snatching rationed goods, like sugar and cigarettes, from the factory cafeteria. Slacking — a practice so common during the war that there was a propaganda effort to counteract it — was almost inevitable in such a high-pressure environment.

In February of 1942, Link drafted a memo to employees as a general reprimand for reports of stretching break times and washing up on company time.

“We are being asked to WORK and SWEAT for a few hours each day,” Link wrote, “while [soldiers] are being asked to FIGHT and BLEED — yes, and DIE — any hour of the day or night.” The memo ended with a call for employees to shame idlers by setting a good example.

Flying by the Stars

It was during this period that Link Aviation made its second great contribution to the war effort — one that would help pilots fly by the stars.

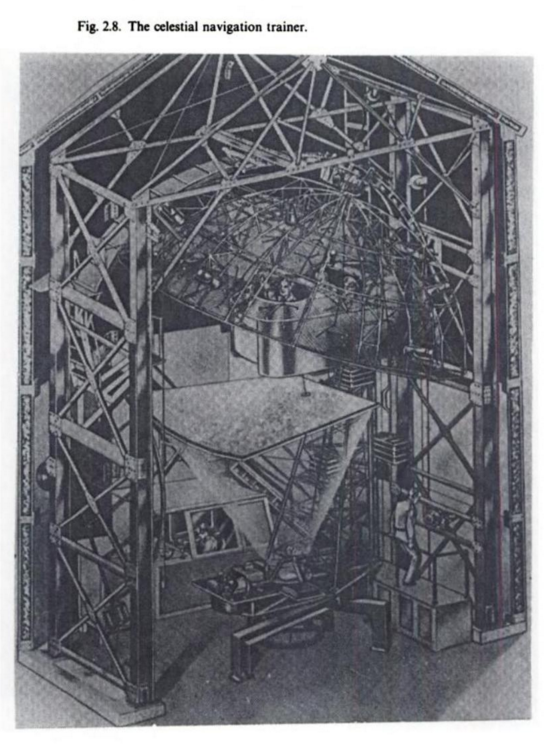

In 1939, a contact in the Royal Air Force suggested that, in the coming war, night-flying would be a major component of strategic bombing and clandestine movement. Link jumped on the idea, and in December of 1942 filed a patent for a “Celestial Navigation Trainer” (CNT) designed specifically for the RAF.

Unlike the ANT-18, the CNT had its own building — a massive concrete tower resembling a grain silo. A mock-up bomber fuselage hung suspended inside, with seats for a pilot, a navigator, and a bombardier. Above their heads, a rotating dome set with star patterns simulated the night sky.

During sessions, the pilot kept the plane level while the navigator used a sextant to plot and track their general position by the stars. Meanwhile, the bombardier could look through his scope and see images of a target scrolling past. This was a major improvement from the RAF’s previous training, which involved shipping pilots to Ontario for dangerous, real-world instruction. To help crews remember the constellations, Link printed star charts on photos of naked girls — the stars strategically preserving their modesty.

“Their popularity was enormous,” one writer recalled. “Few RAF navigators thereafter ever forgot the position of the star they needed to aim their sextant at.”

Link’s Celestial Navigation Trainer made training accidents much less likely — yet still gave Allied pilots the necessary training to find targets and ferry VIPs — including Winston Churchill — under cover of night.

Winning the War

Link Aviation turned out 10,000 ANT-18 simulators between 1940 and 1945. By the end of the war, 500,000 U.S. pilots had logged hours in the “Blue Box,” with the system probably having trained a further 500,000 pilots worldwide.

But the Link Trainer’s real contribution was in what it saved.

During the war, every U.S. pilot was required to log 25 hours in an ANT-18, a policy that spared the Allied war effort an unimaginable amount of fuel. This was no mere financial advantage, either. Every branch of the Allied militaries ran on petroleum, and every gallon saved in training meant a gallon available for the tanks, bombers and aircraft carriers at the front.

It also saved lives. While we think of combat deaths as the main source of casualties in WWII, training was itself a deadly business. Over 15,000 Army Air Corps crew died inside the United States during the war, most in training accidents. But with the Link, every mistake a trainee made on the ground could theoretically head off a mistake in the air — where the consequences were graver. Without the ANT-18 and CNT, it’s possible training casualties might have been higher.

The Link Trainer made social impacts, too. Because the U.S. military needed men for combat roles, WACs and WAVES (female soldiers and sailors) often served as flight instructors. For many women, training cadets on a Link was the first time they held a position of authority over male colleagues.

“We got quite a bit of flak [at first] – whistles, remarks, a little harassment,” says Mary Kessel, a WAVE who trained Navy pilots on the ANT-18 and CNT. “But it subsided. It didn’t ever bother me. We laughed it off.” By the close of the war, WAC and WAVE flight instructors were an accepted part of the military — respect formed over a Link radio.

Pioneering Simulation

While there was worry Link Aviation would go bankrupt after the war, the military’s continued need for simulators helped the company through the postwar period. In fact, Edwin Link’s company still makes flight simulators for the U.S. military. Modern Link simulators look nothing like their bellows-operated predecessors — they’re immobile F-18 and F-22 cockpits with landscapes projected above them — but the tradition lives on.

Edwin Link himself stepped away from the company in the 1950s. He strongly believed simulators should replicate the “feel” of flight, and once fixed-position, screen-based simulators became the norm he lost interest in favor of a new love — underwater exploration. He went on to invent multiple submarines, explore a sunken city off Jamaica, and develop an interest in alternative energy.

***

The Link Trainer’s remembered as a central part of aviation history, but is rarely spoken of as a precursor to games and interactive media — and that’s wrong.

The Trainer was one of the first electronic machines that tried to approximate real-world conditions for the sake of learning and iteration. Later models, like the C-3 and ANT-18, allowed instructors to essentially act as level designers, charting out a flight plan, triggering scripted events, and “killing” the trainee when they deviated from objectives. Incredibly, Edwin Link even struggled with the question of whether simulation could feel convincing without the physical sensation of motion — a question we’re suddenly grappling with as the industry breaks ground in virtual reality.

If you want to see a Link Trainer, you have many options — they have pride of place in air museums around the globe.

Perhaps one day, we’ll see one in a game museum as well.